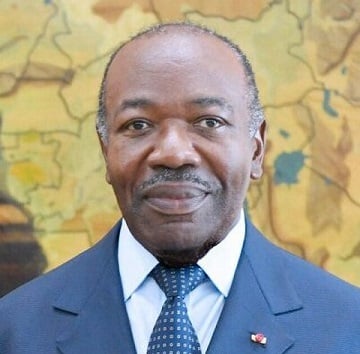

Photo: President Ali Bongo, deposed after 56 years of Bongo rule - Wikimedia Commons

On 30 August, Gabon's army chief announced through a televised address having taken power in the country. Just before that, Ali Bongo was declared president for his third term. "On behalf of the people of Gabon, we have decided to keep the peace by bringing the current regime to an end." The coup follows in a series of successful military coups in six countries since 2020. There is every indication that we are facing a trend of coups taking place in former French colonies in West and Central Africa. Experts also speak of a 'Francophone Spring'. But are these developments entirely attributable to this broad discourse or are we wrongly lumping everything together? What about the local context of these countries. After all, diversity between countries should not be forgotten.

End of Françafrique in sight?

The geopolitical context in the region undoubtedly plays a role in the many coups. Anti-French sentiment growing significantly in recent years and has led to successful coups in Mali, Chad, Guinea, Burkina-Faso, Niger and now Gabon. The people are fed up with the long arm of France. The above countries may have forced independence in the 1958-1960 period, but they still feel that their countries are being exploited by the old colonial power. The unequal relationship between France and its former colonies persists - also known as 'neocolonialism'. French companies act in their own economic interest and in many cases hold the purse strings when it comes to exploiting the many natural resources the countries are rich in, such as uranium, oil, gold and other minerals. The colonial legacy can also still be felt in the financial system. For instance, the CFA franc, the currency introduced by France during colonial rule, is still linked to the European Monetary Union and formerly the French bank. As many as 14 countries are still "held" in this way by a monetary imperialist France. People are also critical of France in terms of security. The military presence under the guise of counterterrorism, only seems to make the situation on the ground worse. Counterterrorism seems ineffective in the way France uses it, namely military symptom control instead of addressing the 'root causes'. The breeding ground is not being removed while creating more instability and increasing grievances against France which then makes people more inclined to join terrorist groups. It is even believed that France is deliberately trying to keep the region unstable for its own gain. Coup leaders then pose as anti-French and anti-colonial to garner public support.

Where one superpower leaves its prominent position, the next is often eager to fill the resulting vacuum. Russia sets itself up as liberator and Stresses common will to counter neo-colonialism. It presents itself as a worthy alternative to the West - the shared enemy. Russian troops are embraced by the new ruling regimes because they can support them in retaining power.

Safety not guaranteed

Besides geopolitical influence, a common trend can also be observed at the regional level. Terrorist groups have found their way to the African continent and in particular the Sahel region - a range of countries across the breadth of the continent on the Saharan border. Instability, poverty and corruption create a very fertile breeding ground for terrorist groups. Groups that form from local grievances but also groups that align their narrative with more global movements like IS and Al-Qaeda, usually not for ideological reasons but because of the large network involved. As many as 48% of terrorism-related deaths occur in sub-Saharan Africa, more so than in the Middle East. The Sahel faces the world's fastest-growing and deadliest terrorist groups. The threat of terrorism is used by many army leaders as legitimisation to intervene and take over power in the country. Indeed, the belief is that current governments are failing to protect the population. A strong, military approach does appeal to the vulnerable population in many cases. This trend is at least true for the Sahel region, to a lesser extent for Gabon specifically where terrorism has not yet penetrated society. Yet it is telling that the places where it is a problem show a similar trend.

Domestic grievances

Having highlighted the above, it seems evident that the series of coups follows from a shared set of causes. However, it is too short-sighted to argue that these are the causes. Developments in countries are never fully produced by global trends alone. The hugely globalised world sometimes makes us all seem to be part of a structuralist system that you as a country cannot influence, but the local context still plays a major role. Dissatisfaction with national government and anger over negligent policies also play a part. Corruption plays a big role in turning against the government. Thus, the large amount of money earned through natural wealth does not end up with the population, but in the pockets of the elite. Large sections of the population live in poverty despite the wealth present in the land.

The most recent and also underexposed coup, that in Gabon, also certainly had local causes. Presidential elections took place the week before the coup. Ali Bongo, son of Omar Bongo who ruled the country for 41 years until his death in 2009, won and would run for his third term. Bongo would have secured 64% of votes, compared to 30% for opposition figure Albert Ondo Ossa. The election was labelled unreliable by the opposition. Shortly after the elections, the Internet shut down, a curfew imposed and international media banned. Combined with a limited presence of international observers, this made the elections anything but transparent. The rigged elections were the straw and the army leadership took control.

Not all coups are the same, but there are clearly common causes. The underlying, often long-standing bubbling dissatisfaction with the regional and geopolitical situation plays a major role in potential coups. However, it is dangerous to get overwhelmed by global trends and always point the finger at structural developments. It is the combination of factors at all three levels together that create the right conditions for a coup. Gabon, at first glance, seems to fit nicely into the series of coups in West and Central Africa, but the local context of dissatisfaction with an authoritarian regime ultimately initiated the coup. Thus, a specific, local motive can be detected in each coup that makes the situation unique. However, the recent spate of coups may inspire countries in the region with similar political contexts, making another coup elsewhere increasingly plausible.