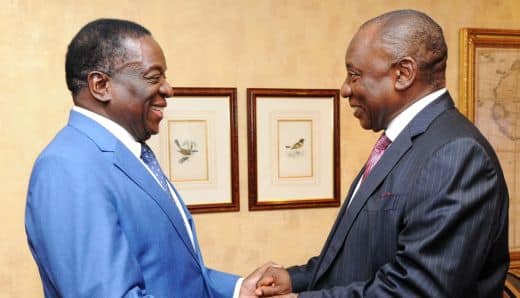

"The question we do not know the answer to is: does leadership change also mean a regime transition?" Recent events in Zimbabwe may mark a 'turning point' for the whole of southern Africa. But is the leadership change from Robert Mugabe to Emmerson Mnangagwa enough for that? A well-attended event called "A new era? Understanding Zimbabwe's transition" took place, where this question was discussed under the watchful eye of an interested audience and specialised panel. ASC director Jan Bart Gewald kicked off the meeting with a personal account of his own experience and affinity with Zimbabwe. He called the recent events of November 2017, growing up as a boy in 1960s criminal Rhodesia "close to his heart".

The first and immediately the most fascinating part of the discussion was that of Zimbabwean political scientist Professor Eldred Masunungure. In a very evocative manner, he gave both his opinion on recent developments, as well as developments to come. Before he began, he said, "I'm not here as a war collaborator but as a professor of Political Science". Having said that, he started his talk and expressed his concerns about the uncertainty following the November coup. The "coup" or as the professor himself preferred to call it "the military aide of intervention" has stirred a lot among the people. Since 1980, it has been the ZANU party in power with very little opposition. "The opposition has no plan of action," says the professor. That the military is very popular in Zimbabwe is proven by the demonstrations and 'solidarity marches' following the coup.

"a broken society, broken economy, a broken everything"

Whether Mnangagwa can give the people the change they hope for remains to be seen. Mugabe's "long life allay" as Professor Eldred calls Mnangagwa is already showing different behaviour from what we were used to seeing from him before 17 November. "He prefers to be feared than loved" is how Professor Eldred describes the new Zimbabwean president. Despite doubts about his sincerity, the professor does speak of an important choice by Mnangagwa to make changes in the economy rather than politics. The election will not be a 'gamechanger' but the economy can.

But popularity and support for the army has also declined rapidly in a few months. The people are disappointed. Yet, according to the professor, this disappointment is unfair. A country with "a broken society, broken economy, a broken everyhing" is difficult to fix in 3 months. The professor captures the imagination when he compares the situation to post-Mao Zedong China or unchanged Cuba. The question of where the new regime stands will have to be decided by the elections in July this year.

The need for cooperating agencies

Corruption is Zimbabwe's biggest problem, according to the professor. He says all international organisations must now start working together to ensure that elections will be transparent and fair and that 'civil society' is protected. According to the professor, there are plenty of indications that Zimbabwe's government wants to do something about this, but their actions are currently less than their words.

The afternoon ended with a panel discussion and questions from the audience. The panel included Judith Sargentini, GroenLinks MEP, Emma Beelaerts van Blokland, Zimbabwe desk officer at the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Hugo Knoppert, coordinator of the Zimbabwe Europe Network (ZEN), a network of more than 25 European 'NGOs working in Zimbabwe. The panel discussion unfortunately came across as somewhat politically correct but muddled. It was about the Netherlands' 'wait and see' approach to Zimbabwe and how the Netherlands is likely to follow Europe in particular.

Are Zimbabweans themselves delaying a 'revolution'?

In the absence of questions from women in the audience, I decided to use my own experience in Zimbabwe to ask the professor a question. I wondered to what extent Zimbabweans themselves could be held responsible for delaying a 'revolution' in the country. Professor Eldred responded that Zimbabweans are indeed more passive than active and they often respond individually to a collective problem, but that they were also, to some extent, not allowed to for fear of taking to the streets. During the time I lived in a suburb of Harare, I also felt this fear. I hope recent events have made it possible to talk more openly about politics. The Q&A with the audience then quickly shifted to the recent incidents surrounding South Africa's new president Ramaphosa. There are also doubts about Ramaphosa. Time will tell whether there will be real change in Zimbabwe. The promised elections in July will tell us more about this.

By: Hannah Deelstra

Photo: Flickr