By Merel Maurits

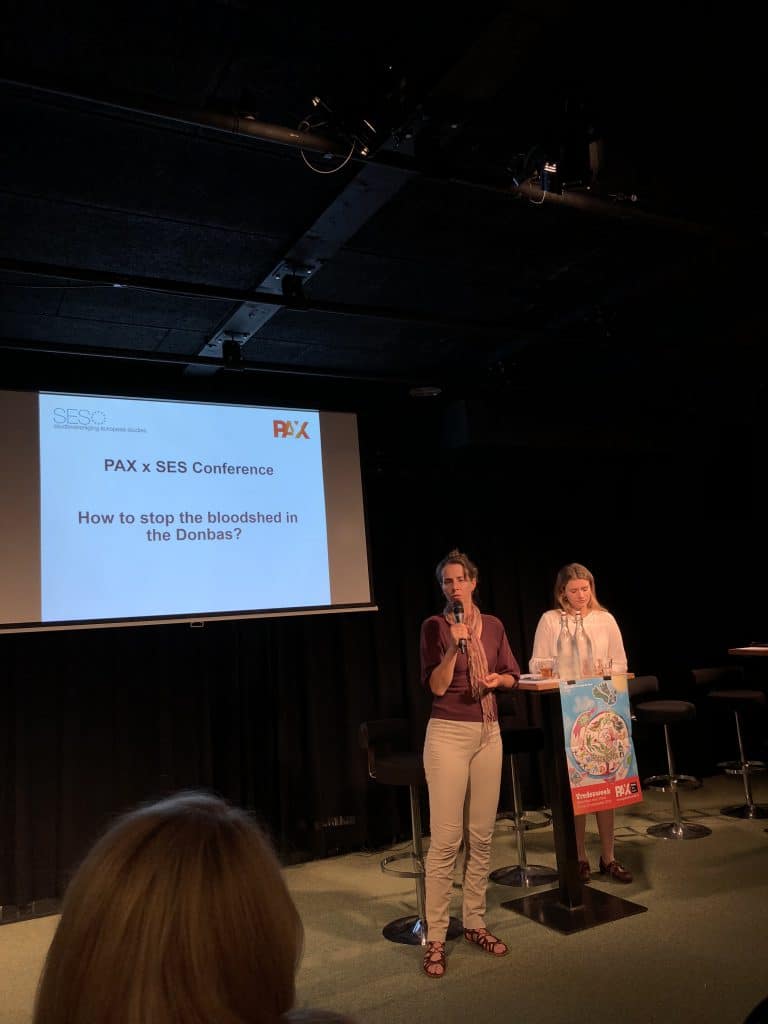

On 18 September, during PAX Peace Week, PAX organised a conference in collaboration with SES (European Studies Study Association) around the question: 'How do we stop the bloodshed in the Donbass?'

Experts from different regions in Eastern Europe and the Western Balkans had come together for the event to come up with concrete solutions to the conflict in eastern Ukraine. They presented their findings at the mini-conference in the evening.

Without any prior knowledge, the story would have been difficult to follow. An introduction was missing and certain jargon terms and abbreviations were not explained. Several experts[1] spoke, but mostly limited themselves to their own experience in the conflict they were involved in, without making the connection to eastern Ukraine. There was a real story missing about a targeted approach to eastern Ukraine.

The experts speaking seemed to agree on one issue: Russia is the aggressor in eastern Ukraine, and without Russia's cooperation and consent, they also believe there will be no solution. However, Russia still denies (direct) involvement in eastern Ukraine, but the EU and the US judge otherwise. In response to the violation of Ukraine's territorial integrity, sovereignty and annexation of Crimea, the EU and the US introduced sanctions. Recently, 13 September, the EU announced extension of the current sanctions until March 2019. The conflict in eastern Ukraine is still unresolved and the question that can be asked is whether the measures contribute to resolving the conflict.

Sanctions

Sanctions are used to condemn the behaviour or certain actions of another country and to make reprehensible policies more difficult to implement. It was not the first time the West imposed sanctions on Russia, but today it is difficult to achieve the desired result, especially as we live in a globalising world and Russia is not solely dependent on the EU and the US. As a superpower, Russia can easily seek rapprochement with other countries, although it is not easy to replace the EU and the US as they are the biggest economic powers and also Russia's main trading partners.

The sanctions initially targeted specific individuals and companies, but as the conflict in eastern Ukraine dragged on, the measures were expanded. The assets of 155 individuals and 44 companies have been frozen and travel restrictions imposed. There are also measures banning access to the EU capital market and an embargo on the import and export of arms-related goods. However, Russia's main export products, oil and gas, are almost entirely excluded from the sanctions, as Europe is partly dependent on them.

Consequences of sanctions

Measuring the economic impact of sanctions is complicated, especially in the case of Russia, as its economy was already stagnating in the period when sanctions were introduced (2013-2014), this due to falling oil prices. According to calculations by The Bank of Finland Institute for Economies in Transition, sanctions contributed to a fall in GDP by 2-2.5%, which many experts consider relatively little. Russia lost its main trading partner due to the sanctions, but is quickly trying to adapt by seeking alternatives, for instance in Asia. With China as a new trading partner, they can absorb some of the damage. Furthermore, Russia is benefiting from recovering oil prices, gradually increasing revenues again.

Not only are the economic effects difficult to measure, but it is also difficult to assess how and whether the sanctions affected Russian foreign policy. According to many experts, the sanctions were not aimed at reversing policy (annexation of Crimea), but at preventing military escalation, condemning behaviour and encouraging a diplomatic solution, such as the Minsk agreements. Military escalation, such as the capture of the city of Mariupol in south-east Ukraine on 28 August 2014, was prevented by the sanctions, according to Edward Hunter Christie (NATO economist).

A diplomatic solution to the conflict has not yet been achieved, nor has implementing the Minsk agreements. Measures against Russia have been in place for four years and are still being extended. While the economic consequences so far seem to be not too bad for Russia, they may still be felt (better) in the long term. Meanwhile, the threat of extending sanctions does cause de-escalation in eastern Ukraine. Either way, sanctions can be a painful and effective tool, but results are often not quick. It is therefore for the long haul.

[1] Robert Serry (former Dutch diplomat in the Middle East, Afghanistan and Georgia) , Paata Zakareishvili (former-minister of Georgia), Katarina Kruhonja (peace activist from Croatia), Andrew Wilson (professor of Ukrainian Studies at University College London)