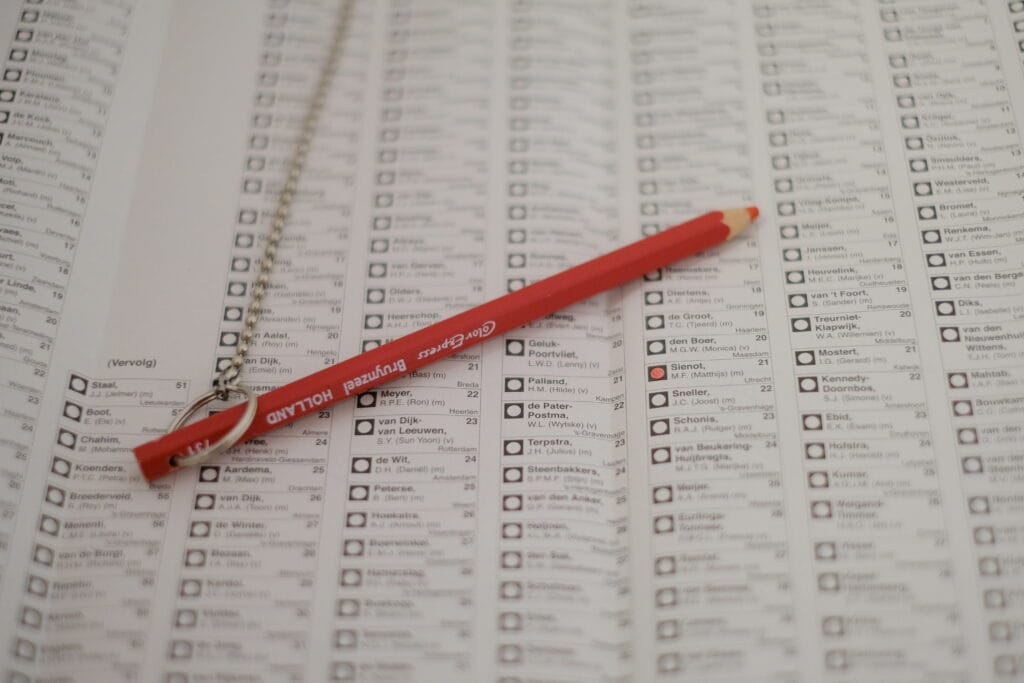

Photo: Ballot paper for the 2017 elections - Wikimedia Commons

How do you process experiences from an authoritarian regime in a country that runs on democratic rules of the game? For many people who grew up in Syria, this is not a natural process. In this piece, Syrian journalist Hasan Kaddour describes how distrust of authority, formed in a context of repression, can also permeate the Netherlands - and how it sometimes manifests itself in silence.

From fear to silence

During a telephone conversation, I asked a Syrian refugee also living in the Netherlands about how he was doing and how he was living. He hesitated for a long time before saying anything, and finally whispered, "Please, don't write anything about me... I don't want the municipality to get angry with me."

He did not complain about a corrupt government or gross injustice. His only wish was more space for his family of eight, living in a flat of less than 60 square metres. And yet he was afraid. Not of me as a journalist, but of the municipality. To him, the Dutch town hall - a symbol of service - resembled the security service he fled in his homeland. Where fear resides in the body, even after the flight.

Politics is taboo

Arriving in a democratic country does not automatically mean that a person becomes a democratic citizen. Years of living under oppression teaches a person that any authority can be a threat, and any state agency is an extension of the secret service. "In my mind, the police are still linked to arrests. I cannot ask them for help even when I know they are not like the Syrian police. Fear is deeply rooted." He adds, "When a police car stops next to me, I feel my heart sink into my shoes... Those who have lived among snakes for a long time are afraid of even a rope."

Ask a Syrian refugee for his opinion on elections or local politics, and he turns away - as if the question itself is dangerous. A young man from Idlib says: "Politics has nothing to do with me. I learned that it drowns you out. When I vote, I do it quickly, as if it is an obligation. I choose a party that religiously resembles me, so I feel comfortable and can move on again." Some even admit that they vote out of fear, afraid of being punished later by the government or the municipality.

This is not an incident, but a broad pattern within the Syrian community. The phrase "the walls have ears" is heard not only in homes, but also in cafes and parks. Ordinary conversations are whispered, as if a security report is in the air. A 40-something from Damascus cautiously says: "In Syria, we didn't trust anyone. And here? Not much has changed... One word can bring you down. The only difference is that the prisons here are cleaner - but the fear remains."

The municipality as a symbol of power

Whereas in the Netherlands the municipality is seen as an approachable, service-oriented body, in Syrian memory it evokes something quite different: administrative power. A visit to the town hall awakens memories of army service or political security service. A neat official? In a refugee's mind, he might be an "officer" in a different suit.

A Rotterdam resident says: "Every time I go to the municipality, I feel I am being tested. Even if I need a simple form. I am afraid they will refuse my request, or open a file I don't understand."

This creates a defence mechanism: no complaints, no demands, just silence and avoidance. And that is where the cycle of democratic exclusion begins.

The law as cultural shock

Even when the language of institutions is clear, a deep divide remains: the law itself. The Syrian refugee comes not from a rule of law, but from a system in which the law was a facade -a weapon in the hands of power. There is a cynical phrase in Syria: "The law is made to be broken." That phrase resonates both with those in power, who deploy it, and with the people, who have adopted it as a cynical reality. Thus grew the realisation that the law is not a shield, but a trap.

In the Netherlands, the law is the backbone of everyday life - a social rhythm. Not only in government institutions, but also in family life. Eating on time, scheduling appointments, raising children without shouting; parents negotiate instead of rule. Here, rules are not a threat, but foundation.

So when it is said that refugees "do not respect the law", it is not rebellion, but because they have never lived in an environment where the law is respected and above everyone else. It is not disrespect, but a cultural shock that takes time and bridges of patience, not accusations or simplifications. Of course, this experience cannot be generalised on all Syrian refugees, but what is recounted here reflects a common and profound pattern that recurs in various forms.

Photo: Hasan Kaddour

From integration to coexistence

The concept of integration seems exhausted. It often suggests a fixed model into which the refugee must blend. As if participation only counts when you adapt and partially give yourself up. What we really need is coexistence: a social fabric that leaves room for difference, like Eastern damask. Each thread different, but together a cohesive, strong whole.

Making the refugee part of that fabric is not done by repeating laws, but by involving them in understanding, applying and even thinking about legislation.

A practical approach: how do we build a healthy relationship with the law?

Imagine: a sunny afternoon, a meeting between refugees and municipal employees. No instructions, but an open conversation about rights and duties. Misunderstandings are discussed, and the human faces behind the authorities emerge. This is followed by a workshop: daily life under the law. No dry rules, but lived experiences. People share their first encounter with the system, their fears, and how they overcame them.

Then a guidance programme: volunteers help families with their first legal steps - from residence application to municipal registration. Not a bureaucratic maze, but a path with guidance.

And finally: invitations to participate in neighbourhood councils, neighbourhood meetings, or public space projects. This way, people feel: I am not a file, but a participant.

From own threshold to shared pavement

The late British journalist Robert Fisk once wrote: "Arab homes are spotless, but their streets are often repulsive, with dirt and excrement lying on the pavement." His point: under authoritarian regimes, there is a separation between private space - which you own yourself - and public space, which is considered the property of the state. That separation leads to behaviour in which people respect their threshold but ignore the pavement.

Democratic citizenship requires repairing that breach. Those who dare to see the pavement as part of their responsibility also dare to engage in political participation.

From fear to action

In Syria, we did not dare to walk on the pavement opposite the security building. We bowed our heads and quickened our steps. In the Netherlands, politics is that pavement. We dare not come closer.

If we truly want an inclusive democracy, we need to build bridges between experience and system, between fear and engagement. Not just through policy, but through relationship.

Politics still feels like a military zone to many. And democracy? A fond dream, watched from the sidelines, without crossing over.

We must ensure that newcomers feel that this pavement is not a trap, but the beginning of a road. That ballot boxes are an invitation to make their voices heard, not to judge their intentions. That the municipal official changes from a symbol of power to an ally. That the refugee does not think participation is a dangerous crossing, but a safe return to dignity.

Because ultimately, democracy is not a geographical destination, but a courageous relationship with yourself and others - starting with a step... on the pavement.