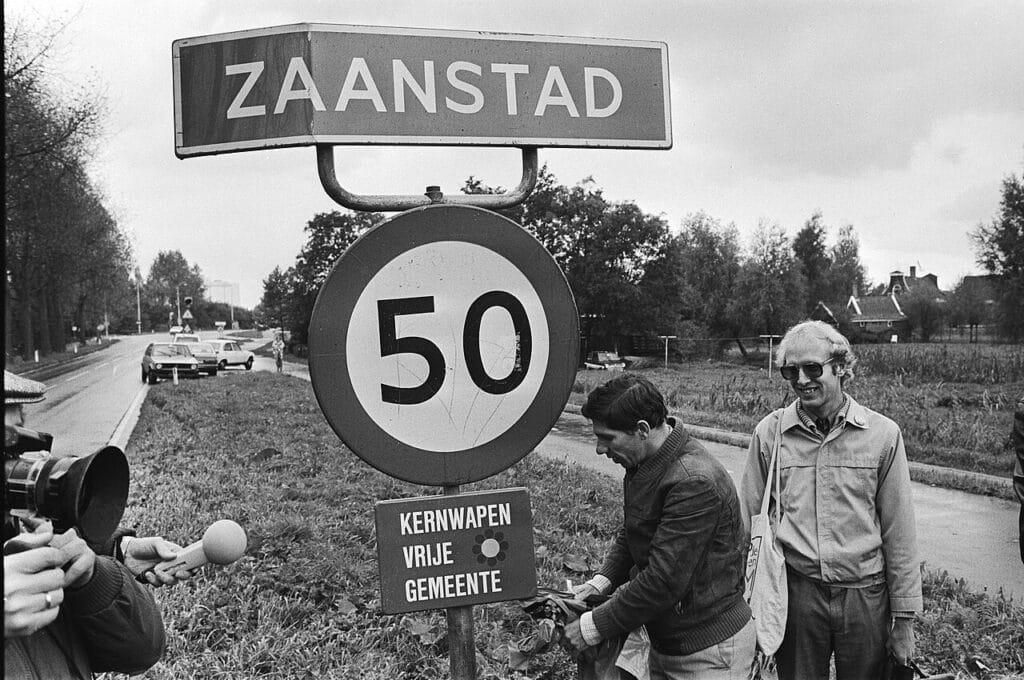

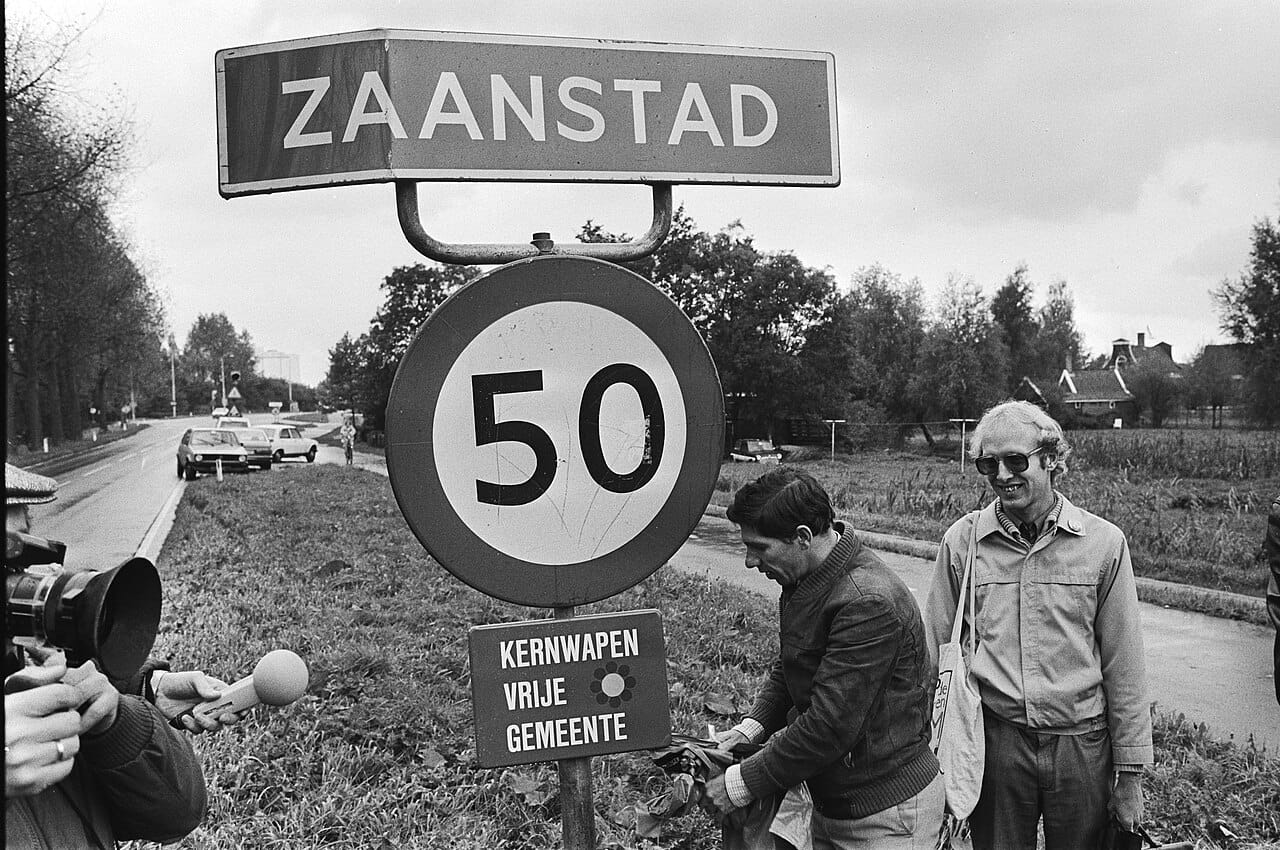

Alderman Nieuwenhuizen unveils a “Nuclear-weapon-free municipality” sign in the municipality of Zaanstad in 1982, the first municipality to do so. On the right Nico Schouten of the action committee Stop the Neutron Bomb. Source: National Archives.

In view of the upcoming municipal elections on 18 March, FMS recently organised a political café on the impact of local politics on foreign countries: ‘local goes international’. I chatted further on this topic with Dion van den Berg, peace activist and former policy advisor at PAX. Together with Peter Knip, historian and former director of VNG International, he published a book in January on the formation of municipal international policy from World War II to the 1980s. How can we flesh out major international issues locally? And what can the past teach us about today's efforts?

The international role of municipalities

Most people will not immediately think of municipal policy in terms of its role and influence beyond local, let alone national, borders. Yet historically, municipalities have indeed dealt with international issues and played an influential role at the international level at key moments. In their book, for instance, Van den Berg and Knip describe how municipalities, among other things, maintained city ties with Warsaw Pact countries during the Cold War and after the fall of the Berlin Wall, participated in economic boycotts against the South African apartheid regime, or entered into knowledge exchange projects with municipalities in ‘the Third World’. Municipalities that pioneered such initiatives could not always count on support from the state, nor, in the first instance, from the Association of Netherlands Municipalities, which for a long time did not consider the international domain to be part of the municipalities‘ remit. Certainly not when it came to ’politically sensitive' matters.

“I have often enough seen so-called ‘experts’ going to advise local governments abroad when, with all due respect, they had the balls to understand local governance.”

However, according to Van den Berg, for municipalities right an important role at the international level: “Local governments are experts on local governance and local democracy,” he tells me. “If you want to achieve something from the Netherlands abroad at the local government level, it is valuable to involve the expertise of local governments on the Dutch side. That is specific expertise they often don't have at ministries and development organisations.”

This municipal expertise can be of great value in post-autocratic countries or in countries where democracy is under pressure, according to Van den Berg: “If you want the voice of citizens to be strengthened in change processes, that local government is particularly important. That is the government that citizens deal with the most. It is worthwhile to see if, as a municipality, you can support local governments elsewhere that want to develop more democracy again after a period of dictatorship or democratic decline.” Those connections from municipality to municipality are an important form of “international solidarity”, according to Van den Berg.

In addition, because municipalities are in direct connection with higher levels of government, they can be an important link between citizens and national governments in initiating broader national and international change processes from the bottom up. “Local governments are important not only to support national governments and implement national legislation, but also to correct or call for different policies. That is part of a mature democracy,” Van den Berg said. “It is extremely legitimate for municipal councils, mayors and aldermen to express sentiments that are widely felt in the local context among their own citizens.”

A new interpretation of international solidarity

Yet, according to Van den Berg, municipalities can do more today to reshape their international role in a politically relevant way. According to Van den Berg, in the 1970s and 1980s, municipalities were much more called upon to actively engage with international issues than is the case today. Whereas previously municipalities acted internationally out of a sense of international solidarity, today, according to Van den Berg, municipalities mostly maintain international connections out of “enlightened self-interest”, with the economic development of their own community taking centre stage. The realisation that things can be done differently seems to have subsided.

For instance, after the initial reaction of some municipalities in response to the Red Line demonstrations, concrete action from Dutch municipalities remained largely absent. How different it was, says Van den Berg, after the nuclear weapons demonstrations of 1981 and 1983 when a large number of municipalities deliberately formulated a municipal peace policy: “It was quite broad what municipalities undertook and certainly not all heavily political, it included, for example, support for local peace groups, consultations with schools for peace education, subsidies for exhibitions and meetings, but also municipal contacts with Warsaw Pact countries.” Although Van den Berg says there is little point in being nostalgic about those days, he says it is worthwhile for municipalities to work with citizens to redefine international solidarity.

Municipalities could encourage more dialogue on anti-Semitism and discrimination at the local level, in addition to considering how they could shape concrete international action regarding Israel and Palestine. With regard to Ukraine, Van den Berg said municipalities could start playing a supportive role not only in rebuilding physical infrastructure, but also in re-decentralising governance and rebuilding local democracy. “Perhaps the central theme now, also for local governments in the Netherlands, is ‘how do we keep democracy afloat?’,” Van den Berg argues. According to him, municipalities could engage much more in the conversation about this with local governments elsewhere in the world, including in emerging countries such as India, Indonesia and South Africa.

Still, he wants to be modest when it comes to prescribing what municipalities should concretely undertake, Van den Berg stresses: “That is for municipalities to determine together with citizens.” On the one hand, municipalities could draw more from, and create space for, local civic initiatives. On the other hand, social initiatives could also appeal more to municipalities and insist that they formulate clearer policies on international issues. “That social infrastructure for international solidarity needs to be rebuilt,” Van den Berg argues.

Change starts with the individual

That this, according to Van den Berg and Knip, holds a responsibility and an opportunity for each individual is evident from the personal approach of their book. A major motivation for writing the book was to pay tribute to the people who stuck their necks out from the Second World War onwards to set up municipal international policy, says Van den Berg. The book therefore features several inspiring portraits of people like Huib van Walsum, Hilda Passchier, or Cor de Vos, who personally committed themselves to this.

“Show me your diary and I will tell you what you can do.”

When asked how people can make a difference locally in these geopolitically turbulent times, Van den Berg replies with optimism: “Show me your agenda and I will tell you what you can do. You have to try to make things that you yourself are enthusiastic about connect internationally.” This can be done as a city councillor, but also in the theatre world, at the local sports club or at a chess tournament, Van den Berg says: “More is often possible than people think.”

Want to learn more about the history of municipal international policy? The book by Dion van den Berg and Peter Knip; ‘World beaters we were’, is this page available.